Back in September, a pipe burst in my son’s bathroom. Believe me when I say water is a force, and it soaks into walls fast! The mitigation company chopped holes through ten walls and installed fans to prevent mold. Next, our hot water heater broke, spewing water everywhere. Yet more holes! Then a pipe burst in our attic. Our plumber showed me the broken pieces: “This is cheap pipe, Karen. It’s going to keep happening.” We got the message: we needed to repipe our entire house. The plumbers cut yet more holes. (!!) There was dust everywhere. In a word: disruption.

It felt like an apt metaphor for my writing life because with Down a Dark River, I realized—in retrospect—I had to do the authorial version of cutting through the drywall, taking out some old pipes, and putting up with dust during a slow rebuild.

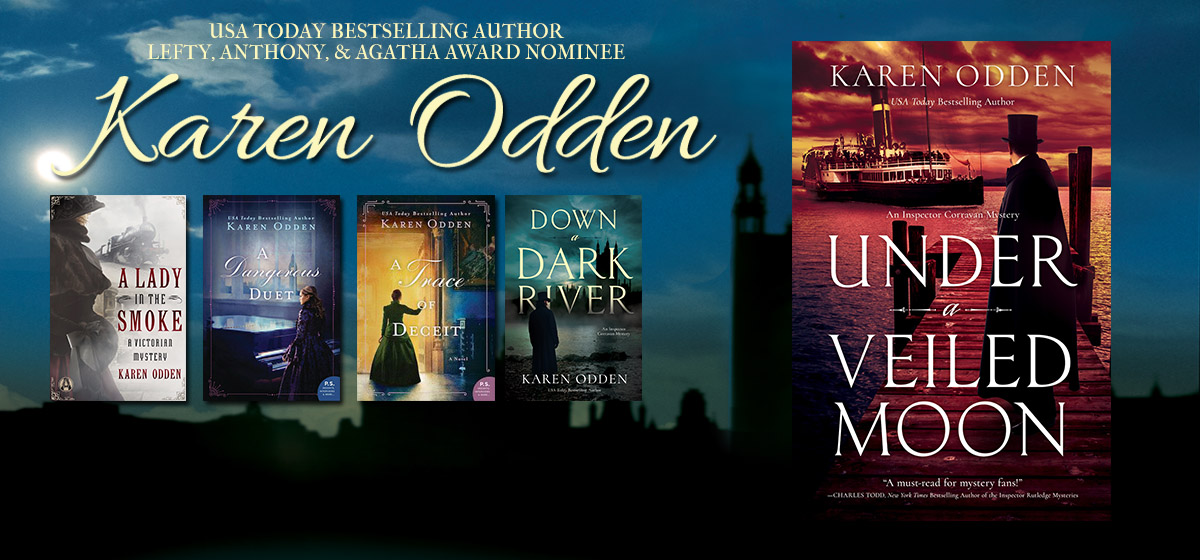

All my books are set in the world of 1870s London, a period I’ve researched extensively beginning with my dissertation at NYU. My first three novels feature different young women protagonists who become amateur detectives because someone they love has been injured or died. These books tend to be intimate, with deeply personal stakes, and follow in the vein of some old favorite books by Mary Stewart, Daphne DuMaurier, and Phyllis Whitney.

But then I came across a story that clawed at me and inspired Down a Dark River.

I found it in a contemporary article about race and the law in the US. A young Black woman in Alabama was jaywalking across a quiet street when she was hit by a car, driven by a wealthy white man who was intoxicated. She suffered terrible injuries, and when her family sued, the judge awarded her a piddly $2,000. Outraged, her father took an unusual step: he threatened the judge’s daughter. To my mind, he wanted to show the judge what it was to almost lose a child. I found myself compelled to write a book about failures of empathy and the desire for revenge.

However, if I wanted to set this mystery in 1870s London, I needed male characters. In Victorian England, the judges, the police, and barristers are all men. (Women weren’t allowed into the Met Police or onto juries until around 1920.) So I couldn’t write a book with a young woman amateur sleuth. This was a “rip out the old pipes” moment.

From the beginning, the book felt darker and more ambitious. I dug deeper into my own “foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart” for the ugly moments when I felt the sting of injustice, when I wished for revenge, when I was full of regret for mistakes I made. It was emotionally uncomfortable but creatively productive. To develop Inspector Michael Corravan, I spent hours reading male protagonists in The Bourne Identity, Faithful Place, and the Bosch novels, and Victorian police reports (all written by men, of course) out loud, to train my ear.

For Down a Dark River, and its sequel coming in November 2022, I removed some old writing pipes and put up with some disruption to find new ones. You can’t see them, but I know they’re there, and I feel the difference as I sit down to write.

Readers: Can you recall a time when you’ve had to “reboot” or step backward in order to make progress? Or step out of your comfort zone to grow? I’d love to hear. I’ll send a signed copy of Down a Dark River to one commenter (US only).

NOTE: This blogpost originally appeared on The Wickeds blog, where mystery writer Julie Henrikus hosted me. The Wickeds’ theme for the month was “Out with the old (and in with the new).” Find the blog and comments here: https://wickedauthors.com/2022/01/28/a-wicked-welcome-to-karen-odden-plus-a-giveaway