London, 1875

The back door of the Octavian Music Hall stood ajar, and a wedge of yellow light streamed out into the dark, crooked quadrangle of the yard. I picked my way toward it across the uneven ground, glad that I was in stout boots and trousers instead of my usual skirts. It had rained all day, and I tried not to think about what might be in the muck under my feet.

A tall, broad-shouldered figure stood silhouetted in the doorway: Jack Drummond, the owner’s son, a stolid and taciturn young man who helped build scenery and props and fixed things when they broke. As he’d never said much more than “Good evening” to me, I knew very little else about him except that he let us performers in at the back and then went round to the front door to keep the pickpockets from sneaking in. I felt a secret sympathy for those ragged boys, desperately in need of a few pence for supper. Once the curtain rose, the men in the audience, most of them well into their cups, would be staring agog at a Romany magician or a half-naked songstress or some flame-throwing jugglers. It would’ve been child’s play to find their pockets, and chances are most of the men wouldn’t have missed a coin or two.

Jack touched his cap briefly as I approached. “Mr. Nell.”

“Evening,” I muttered. My voice was naturally low, but to bolster my disguise I pitched it even lower and hoarser.

“Mr. Williams needs to see you before the show.”

My heart leaped into my throat. I’d done my best to dodge the foul-tempered stage manager since he’d hired me weeks ago.

“Did he say why?”

“No. But don’t worry. He didn’t look mad.” His dark eyes met mine, and he gave a faint, wry smile. “Leastwise, no madder than usual.”

I snorted. “Good.”

From the bell tower of St. Anne’s in Dean Street came the chimes for three-quarters past seven. Fifteen minutes until curtain.

“He’ll meet you at the piano,” Jack said.

I hurried down the ramp that led to the corridor below the stage, feeling inside the brim of my hat to make sure that no stray hairs had escaped my phalanx of pins. Then I turned toward the flight of stairs that led up to stage right. The hall above, where the audience sat, had been elegantly renovated a few years ago when the Octavian opened, with crystal chandeliers and paint in tasteful hues of blue and gold. But the rabbit warren of passages and rooms underground was original to the hodgepodge of buildings that had stood here a hundred years ago, when the entertainment on a given night was likely to be bearbaiting and cockfighting, and the animals were brought up from below. The air stank of mold and rust; the plaster was crumbling off the brickwork; and the wooden steps had been worn down so far that the nailheads could catch a misplaced toe or boot heel and send one sprawling—as I knew from experience.

Slow footsteps thudded above me. Jack’s father—whom everyone called by only his surname, Drummond—was coming down. He was a burly man, a full head taller than I, with the same unruly black hair that Jack had, thick black eyebrows, and a cruel mouth. I smelled the whiskey on him as he drew close, and I put my back against the wall to let him pass.

“Evening,” I croaked, same as I’d said to Jack.

He didn’t even glance at me. Motionless, I watched as he descended and vanished into the lower corridor; then I allowed myself a deep breath and continued on my way.

At the top of the stairs, I ducked through a set of curtains to enter the piano alcove where I’d spend the next two hours. My spot was in the corner of the hall near stage right, with a second pair of curtains to separate me from the audience until the show began. The stage, which I could see from my piano bench, was elevated off the hall’s plank floor—wooden boards that had no doubt once been glossy, back before they’d absorbed hundreds of nights’ worth of spilled gin and ale.

From the sound of it, members of the audience had already spilled a good deal of gin and ale down their throats, for they were more boisterous than usual for a Wednesday night. Curious to see why, I parted the curtains slightly and peered out, but nothing seemed out of the ordinary. Some of the men had found seats at the round tables; the rest were still gathered at the bar, where beer and wine and spirits were being distributed from hand to hand.

The room was large, with walls that curved at the back so it resembled a narrow U. According to Mrs. Wregge, the hall’s cheerful purveyor of costumes and gossip, the builder believed that keeping everything in eights would protect against fire—hence the “Octavian.” He was so persistent in this belief that he moved the walls inward by a yard, so that the seating area measured sixty-four feet at its longest point. Eight gas-lit chandeliers sent their glow flickering across the room; eight spiraling cast-iron pillars supported the balcony; and each pillar had twenty-four turns from bottom to top. Perhaps the spell of eights worked because during every performance, glowing ashes from the ends of cigars and French cigarettes dropped onto the floor, and still the building remained intact.

As I did every night, I said a quick prayer that the magic would hold. This job not only paid three pounds a week; it let me finish by just past ten, which meant I could arrive home before my brother, Matthew, returned from the Yard. The coins I earned were forming a satisfying, clinking pile in the drawer of my armoire, and combined with other money I’d saved, I now possessed over half of the Royal Academy tuition that would be due in the fall. Provided, of course, that I succeeded at the audition in a fortnight.

A flutter of apprehension stirred beneath my ribs at the thought, and I suppressed it, turning deliberately to the piano, lifting the wing, and fitting the prop stick into the notch.

It was a good instrument—surprisingly good for a second-rate hall—a thirty-year-old Pleyel, with a soft touch and an easier action than my English Broadwood at home. The problem was that the French piano didn’t care for our climate; it fell out of tune easily, especially when it rained.

I untied the portfolio ribbons and laid out the music in the order of the acts. First came a man who called himself Gallius Kovác, the Romany Magician, and his assistant, the lovely Lady Van de Vere. He was no more a magician who’d learned his trade from his Romany grandfather than I was, and his accomplice’s real name was Maggie Long. She was exactly my age—nineteen—and the natural daughter of a wealthy tea merchant and his mistress.

After their last trick, I would play a selection of interlude music while stagehands rolled the magician’s paraphernalia off the stage. Then I’d accompany a singer who called herself Amalie Bordelieu. Her songs were French, but her accent offstage was pure Cockney, and her curses came straight off the London Docks. I’d heard them one night when she and Mr. Williams had a heated row in her dressing room. From the tone of it—caustic on her side, surly on his—it seemed to me that her anger derived from a long-standing resentment. Amalie was the only one of us who dared confront Mr. Williams; she had that luxury because she was too popular with the audiences to be turned out.

Gallius and Amalie were our only permanent performers; the next few acts of the program varied. To remain novel and exciting, most entertainers traveled among the hundreds of music halls in London, remaining in each for anywhere from a week to a few months before moving on. This week, Amalie had been followed by a group of jugglers, who rode strange little one-wheeled contraptions and threw flaming candlesticks; next came my friend Marceline Tourneau and her brother Sebastian, with their trapeze act; and then, a one-act parody of marriage, complete with a deaf mother-in-law and six unruly children. Over the past two months, I’d also seen a ventriloquist, a group of six German knife throwers, trained dogs, men on stilts, an absurd dialogue between two actors playing Gladstone and Disraeli, three women singing a rollicking verse about the chaos they’d unleash if only they had voting rights, and an adagio in which an enormous man juggled two girls. The final act was always one of London’s lions comiques—groups of men who dressed as swells, in imposing fur coats and rakish hats, twirling their walking sticks and singing about gambling and whoring and drinking champagne. They brought the crowd to their feet every time.

From backstage came the clang of bells, signaling that the show would begin shortly. Where was Mr. Williams, if he needed to see me so badly? And what could he possibly want? I searched my memory for anything I might have done wrong the night before. The show had gone mostly as usual. He’d shouted himself apoplectic because Mrs. Wregge’s cat Felix had streaked across his path backstage, twice. But he was always ranting about something.

I sat down on the bench and lifted the fallboard. The ebony keys had scrapes along their surfaces and the ivories had yellowed. Still, they were keys to happiness, all eighty-eight of them.

I ran a quiet scale to warm my fingers. I hadn’t played more than a dozen notes when I realized that the E just below middle C was newly flat. And what had happened to the B? I pushed the key down again: nothing, and the silence made me groan aloud. Not wanting to risk Mr. Williams’s wrath, I’d bitten my tongue as, with each passing week, I’d had to shift octaves and rework chords to avoid the flat notes. But this was absurd. I would have to convince Mr. Williams to hire someone to fix it, despite his being a relentless pinchpenny.

I put my foot on the damper pedal, heard a clink, and felt a scrape on the top of my boot.

What was that?

Ducking my head underneath, I saw that a long screw had come loose from the brass plate, which now rested on top of the pedal, rendering it useless. With a sigh, I reached in my pocket and took out a farthing coin that had thinned around the edge; it had served as a makeshift tool before. I crawled underneath, pushed the plate into place, and used the coin to turn the screw until it bit into the wood. I ran my thumb over the head; it wasn’t quite flush, but it would have to do for now.

“Ed! Ed Nell!” Mr. Williams barked. “Damn it all! Where the devil is he?”

I scrambled out from under the piano. “I’m right here.”

“Oh!” Mr. Williams scowled down at me, his bald pink pate shining in the light from the two sconces. “There’s a new act tonight. A fiddler. Found him yesterday, busking at Covent Garden.”

Was that all?

“He’s not expecting me to accompany him, is he?” I asked, as I stood and brushed myself off. It was no business of mine who Mr. Williams brought in, but most of the musicians who played near Covent Garden weren’t much to speak of.

“Nah. He’ll be after Amalie. Just give him a few chords.”

I kept my surprise in check. Mr. Williams must think pretty highly of the man to insert him when people were still sober enough to be listening.

“What’s he playing?” I asked.

“How would I know?” He waved a hand toward the audience. “Hope he can make himself heard over that.”

“They’re louder than usual tonight.”

“It’s because of Jem Ace.”

“Who’s—” I started to ask, but fell silent as the curtain parted and Jack appeared, a troubled expression on his face. His gaze brushed over me and fixed on the manager.

“The Tourneaus aren’t here,” he said.

“What do you mean, they’re not here?” Mr. Williams demanded.

I felt surprised myself. Marceline would’ve told me if she and Sebastian were leaving for another hall. They had never missed a show before.

Jack shook his head. “That’s all I know. And Amalie needs to see you. Her new costume is falling off, and Mrs. Wregge says there’s no time to fix it.”

The stage manager turned away, muttering under his breath.

“Mr. Williams—wait—please!” I said hastily. “Is there any way you could have the piano tuned? The keys are horribly flat. Listen.” I played a rapid scale. “And the B isn’t even working.”

He waved a hand. “Jack’ll look at it later.”

Jack sketched a nod.

I bit my lip, not wanting to be rude, but also not wanting to damage the piano further. “Well, you see . . . it needs someone who’s specially trained and—”

But Mr. Williams was already pushing aside the curtain. “Put up with it,” he said over his shoulder. “Nobody but you’s going to notice.” He turned back, his expression sour. “And be ready to switch Amalie out of order—maybe after the fiddler—or she can take the Tourneaus’ spot, if they don’t arrive. Blasted tart and her costumes. More bloody trouble than she’s worth.” Then he and Jack were gone.

Somewhat exasperated, I tugged at the cords that drew back the curtains separating me from the audience. It was mostly working-class men, still jostling into their seats and shouting good-naturedly to the boys who hawked cigars and cheap roses out of trays that hung from around their necks. As I surveyed the crowd, I realized Mr. Williams was right: no one would notice a piano out of tune, much less a missing note. And why should I care if it sounded horrid, so long as the audience was satisfied?

You’re not playing Beethoven at St. James’s Hall, I reminded myself as I took my seat. And what’s more, you never will if Mr. Williams decides that you’re more bloody trouble than you’re worth. You’re not irreplaceable the way Amalie is.

At eight o’clock precisely, two men on the catwalk pulled the ropes to swoop the curtains in graceful waves toward the ceiling. The sapphire-colored velvet with its gold trim had been mended a dozen times by Mrs. Wregge—I’d seen her perched on a stool, her needle flying across the fabric gathered in her broad lap—but in the flickering light, the patched bits were invisible and the velvet looked rich and elegant.

I struck up the dramatic prelude as Gallius Kovác strode onto the stage, his black cape flapping, his tall black hat—rumor had it he’d stolen it from a police constable—shining under the lights, his mustache waxed to fine curled ends. He extended his hand to stage right, and Maggie pranced out in a costume that never failed to elicit whistles from the crowd—a green-and-gold dress cut low to reveal the curve of her breasts. Her black hair was curled into ringlets and pinned up with sparkly combs. Her lips were painted red and her lashes darkened, like the ladies on the postcards from Egypt that hung in the window of Selinger’s Stationers.

Gallius’s first feat was to pull two birds out of his hat. But nine men out of ten were looking at Maggie, not the birds. The feathered creatures flapped up to the rafters unnoticed, while Maggie preened and strutted and winked at the audience. At her feet landed a small storm of roses, sent flying toward her by men who probably thought she treasured the blooms. After her performance, she returned them to the rose boys to sell again, and they split the two-penny profits.

I knew Gallius’s routine well enough to match the music with the tempo of his tricks. So when he pulled a rainbow of handkerchiefs out of his hat, I rolled the chord. When he made Maggie disappear, I made the piano notes deep and trembly. And the crescendo came when she reappeared out of a box that vanished in a cloud of smoke.

His final trick was to run a sword through Maggie’s neck. I asked her once if he ever poked her by accident, and she gave her sly smile. “That sword bends right through the metal collar. I made him show me ’afore I let him get anywhere near me with it—or with any other part of him that pokes, neither.” She laughed out loud, and I felt my cheeks grow warm.

“Well, ain’t you the innocent,” she teased me, winking.

“I’m not innocent,” I muttered. But she was right: I’d flushed again the following night, when I came upon Maggie and Gallius in the murky gloom of the back hallway, him with his hands inside her skirts and her with her arms wrapped hard around his neck.

Gallius and Maggie left the stage, and I played some interlude music, a medley of popular tunes, all the while keeping my eye out for Amalie, or for whoever might appear next. It turned out to be the new violinist, entering from stage right, and I wound up hastily so he didn’t have to stand there waiting to begin.

He was handsome as anything—tall and slender, with silvery blond hair combed back from his forehead, a well-cut mouth, and bones that showed fine yet strong under the stage lights. I put his age at a year or two over twenty. He was dressed in a tailored coat and pants that bore no sheen from wear at the knees or cuffs, which made me wonder what he was doing playing here—or busking in Covent Garden, for that matter.

There was an air about him that made even this audience give him something approximating real attention. He offered a small, formal bow to the crowd; then he set his bow on the strings and began.

It was a piece I’d never heard, beautiful and haunting—and he could play. His bow stroked smoothly and powerfully across the strings, bringing forth the instrument’s sweetness with none of the shrillness produced by a mediocre violinist.

But it was the wrong piece for this audience. These men didn’t want beautiful and haunting. They wanted fast and loud, bright and bawdy, or downright silly. I felt their indifference flare to irritation, even before the grumbling began, and I prayed they’d give him a chance to finish.

Something small and white—a dinner roll—flew past his ear. He looked out at the audience, and I could tell he was surprised. Clearly, he wasn’t used to this sort of reception, but he played on until a turnip hit him square in the stomach. His bow popped off the strings, and across his face flashed a look of uncertainty, followed by a hot flush of shame and anger as the groans and hisses turned to catcalls and laughter.

The sounds made me flinch, and he turned to me, glaring, as if he expected I’d join in the abuse. Once, I would’ve sat there, feeling as helpless as he. But a few weeks ago, when one of the dancing dogs had gone missing and I’d had to fill the time between acts, I’d played “Libiamo ne’ lieti calici,” the drinking song from the first act of La Traviata. The popular opera by Verdi had just returned to London, so the melody was on everyone’s lips, and the audience had cheered lustily for a full minute afterward.

I riffled through my portfolio quickly, hoping that he knew it.

I couldn’t see his expression as I played the opening chords, but by the fourth measure, he was with me, his bow flying across the strings. The words in their English translation ran through my head: Let’s drink for the ecstatic feeling / that love arouses . . . / Let’s drink, my love, and the love among the chalices / Will make the kisses hotter . . .

It was a fine piece of music for a violin, and I softened my playing so that his could be heard, falling completely silent as he drew out the last brilliant chords.

Above the sound of stamping feet came cries of “Bravo! Bravo!” The violinist pointed his bow toward me and inclined his head toward the audience. They roared their approval, and he bowed again and left the stage.

With a small feeling of triumph, I found myself smiling as I played some interlude music to fill the time until the next act–

And then Amalie fluttered in from stage left, wearing a costume that seemed composed entirely of dyed feathers floating at her bosom and around her waist and thighs.

It was outrageous, even for her.

Like every man in the theater, I caught my breath. My fingers fumbled her introduction, even missed a few notes. But the audience couldn’t have cared less. They went wild for her, cheering and shouting. She sang four songs in French, and as usual, dozens of men hurled roses at her, which she gathered up as she exited stage left, amid a rain of pink paper petals dropped from above.

*

The show finished at a quarter past ten, and I put the music into my portfolio and started down the stairs, hoping it wasn’t raining, as I’d left my umbrella at home.

Mrs. Wregge was on her way up. “I say, have you seen Felix?”

“No. Has he escaped again?”

“I had the door open for not half a second, and he dashed out!” She shook her head so vigorously that her chin wobbled. “If Mr. Williams sees him, he’s going to wring his neck—and mine, too.”

“I would think he’d be grateful that Felix catches the mice.”

“And so he should!” she said in a stage whisper. “He has the benefit of a fine mouser, while I have all the worry of keeping the two of them apart.”

I couldn’t help but smile. “It’s your own version of cat and mouse, isn’t it?”

She chuckled ruefully and pointed up the stairs. “He’s not up there, is he? Mr. Williams?”

“I haven’t seen him.”

With a huff, she moved to continue her climb, but I put a hand on her arm. “Do you know what happened to Marceline and Sebastian? They weren’t here tonight.”

“No.” Her kindly brown eyes sobered. “And it isn’t like them to miss a show.”

“No, it’s not,” I agreed, my feeling of misgiving growing. “Well, good night.”

Turning away, I hurried down the stairs—and caught my heel on one of the treacherous nails near the bottom. With a cry, I pitched forward, nearly tumbling to the ground.

“Are you all right?” came a male voice.

Startled, I peered into the dark corridor.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to frighten you. It’s Stephen Gagnon. The violinist.” He came out of the shadows, his pale hair gleaming in the dim light. “And you’re Ed Nell, the pianist.”

My heart began to fall back into its normal rhythm. I cleared my throat. “Yes, that’s right.”

Two stagehands approached carrying a load of bulky wooden planks, and Stephen and I squeezed back against the wall. “We should move,” I said. “They have to bring all the properties through here.”

He motioned for me to lead the way, so I walked toward the ramp that led out to the yard. This part of the corridor was hung with metal lanterns, and by their light I could see him clearly. He was taller than I; his face was clean-shaven, his eyes a rich hazel. He stood with an easy elegance that spoke of time spent in drawing rooms.

“Thank you for what you did,” he said. “I’d have been turned into mincemeat out there.”

“I’m just glad you knew the song,” I said.

“You play very well. I must say I was surprised.” He glanced around us and tapped a few fingers against the water-stained plaster. “This isn’t exactly—”

“Yes, well, I’m here for the money.”

He grimaced. “So am I.”

There was a story there, evidently, but I could hardly ask directly. So instead, I said, “Mr. Williams mentioned that he found you in Covent Garden. Have you studied somewhere?”

“At the Royal Academy, here in London.”

I felt a stab of envy. “You’re lucky.”

“Yes, I suppose I was.” There was a slight emphasis on the last word. “Where do you study?”

“Just—just privately, until last year.” The thought of Mr. Moehler’s passing still pained me.

“Do you play here every night?”

I shook my head. “Mondays, Wednesdays, and every other Thursday. Carl Dwigen, the other pianist, plays the rest.”

His eyes lit up. “Will you be here tomorrow, then?”

I nodded. “I take it Mr. Williams asked you back?”

“Thanks to you. Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays for now.” He shifted his violin case under his arm. “Say, I don’t suppose you could help me pick a few other songs that the audience would like.”

“Of course.” As I looked at him, a thought occurred to me. “You don’t happen to know how to tune a piano, do you?”

“No. I noticed some of the notes were off. Bad luck.” He flashed a consoling smile.

“It gets worse every week. Jack Drummond is supposed to take a look at it, but—”

“Jack Drummond?” he interrupted. “Who’s that?”

“He’s the owner’s son. He does all sorts of work around here. I’m sure you’ll meet him at some point.”

Stephen’s face wore an odd expression.

“Do you know him?” I ventured.

“No, not at all. But I—well, Mr. Williams led me to believe the music hall was his.”

“In a way, it is,” I said with a shrug. “Mr. Drummond is the owner of the building, but he doesn’t have anything to do with the performances. Mr. Williams manages all of us.”

The back door opened, and a uniformed police constable hurried in, leaving the door ajar behind him. He passed us without a glance and headed down the corridor.

“Wonder what he’s here for,” Stephen said.

We leaned around the corner and watched as the constable entered Drummond’s office without knocking.

No one ever did that, so far as I’d seen.

“Could you meet me here tomorrow, before the show?” Stephen asked. “At seven o’clock?”

“I’ll try. I should go now, though.”

“Well, good night, then.” He held out his hand for mine.

I stared at it. Until now, I’d managed to avoid shaking hands in my disguise. But if I ignored his gesture, what would he think? My hands weren’t small, and they were strong with practice, so I took his hand firmly, trying to perform the act as a man would. However, surprise flashed over his face, and he trapped my hand between both of his, turning it over so he could study my palm. My heart sank, and I pulled away, sharply regretting that I’d stopped to talk to him.

His teasing grin faded. “What on earth’s the matter? I’m hardly going to snitch on you, seeing as I need your help.”

I recognized the truth of his words. “I’m sorry. It’s just—they’d only pay me half as much if they knew.”

“If they even kept you on,” he added bluntly. “From what I know, there’s a distinct prejudice against lady pianists. How long have you been here?”

“Nearly two months.”

His expression became admiring. “Well, I hope I’m that lucky.” He bent his head toward me. “What’s your name? Your real name, I mean?”

I kept silent.

“Come on,” he coaxed. “I can’t call you ‘Ed’ now.”

“It’s Nell,” I said reluctantly. Marceline was the only other person who knew the truth. But admitting it to her had been a relief, for we had commiserated over the ways young female performers were at a disadvantage. With Stephen, I only felt a new inequality, a disadvantage that existed on my side alone.

“Short for Ellen?” he guessed.

“Elinor.” I paused. “I go by Ed Nell here.”

“Ed Nell,” he said, trying it out with a grin. “It’s perfect. I could even call you Nelly in front of people, and no one would suspect.”

I gave him a look that made him instantly turn penitent.

“I won’t say a word,” he promised. “I think you were clever to come here looking for a job.” And then, sincerely, “I’m certainly glad you did.”

He intended his words to reassure me, and I managed a smile.

“Well”—he shifted his violin case again—“I’m told I have to find the wardrobe mistress for a proper costume. I’ll see you tomorrow?”

“Yes. Good night,” I replied and started up the ramp.

The constable had left the back door cracked open, and as I crossed the yard, the church bells chiming three-quarters made me start.

How had it gotten so late? And what if this were the one night Matthew came home early?

I quickened my pace along Hawley Mews, trotting past the Crown and Thorn, where jangling piano music and masculine laughter spilled out the open windows. At the corner, a prostitute called out from below the awning of the chandler’s shop. I had already passed her before I realized that her invitation was meant for me. I moved faster, dodging around a pile of refuse before halting at the corner of Grafton Lane.

Usually I went home by way of Wickley Street because it was lit by gas lamps. Grafton Lane was narrow and poorly lit, but a good bit shorter.

Dare I risk it?

A night-soil man, his cart pulled by a nag with heaving flanks, came out of the alley, and after he passed, I peered in. The passage was eerily empty of people, but the clouds from earlier in the evening had mostly dispersed, and the moon, nearly full, cast a generous silvery light. I thought again of Matthew coming home, checking my bedroom, and not finding me there—and I turned in. Following a series of narrow streets, I worked my way roughly westward until I reached quiet Brewer Street, where all the inhabitants’ windows and doors were closed to the night air and its miasmas. With only another few hundred steps, I’d reach Regent Street. There, gritty Soho ended and fashionable Mayfair began, the boundary marked by Mr. Nash’s famous pillars, the ones that looked like something out of ancient Greece but were only stucco painted to look like rare white marble.

I was almost there when a low cry, quavering and full of pain, sounded from a dark pocket between the buildings to my left. My steps slowed. Wary of lingering—I knew enough from Matthew about the tricks that cutpurses could play—I strained to see who had called out. It could be a prostitute, or a beggar, or some unfortunate drunken soul who had fallen on the way home from a pub.

But the next cry was pitched high, like that of a woman or even a child, and it held a note of fear as well as pain.

The moon had edged behind a cloud, but I could just make out a small still form huddled beside a drainpipe. “Who’s there?” I said softly. “Are you all right?”

The only answer was a ragged breath.

I moved forward cautiously, and when the figure remained motionless, I bent down and reached out. My hand touched what felt like a shoulder, muscled but small. A moment later, the moon reemerged, and I could see that the shoulder belonged to a young woman who’d been beaten badly. Her eyes were closed, her face was dark with bruises and blood, and her thick black hair was a matted tangle. I recoiled in horror, pulling my hand back.

Simultaneously I realized who it was.

“Marceline!” I sank to my knees and groped for her wrist. Her skin was cold and her pulse weak, and as I drew my hand away I felt the stickiness of blood and noticed that her arm lay at an odd angle. “My God, what happened?” I whispered.

She didn’t make a sound.

Fearful of hurting her, my hands hovered, not knowing where I might touch. What could I do? Though she was smaller than I, I didn’t think I could carry her.

And where could I take her? How would I get her there? My thoughts leaped and scattered uselessly, and I took a deep breath to tamp down my panic. Think,I told myself sharply. Hysteria isn’t going to help either of you.

Could I take her home? No, that was impossible. How could I explain her presence to Matthew and Peggy?

Marceline gave another low groan, as if she were in agonizing pain, both mental and physical. That decided me. I’d take her to Dr. Everett.

I had rested my hand lightly on her back to reassure her of my presence. She moved convulsively as I bent over and spoke in her ear. “Marceline, I’m going to get help.”

I raced to Regent Street and raised my arm. Two cabs, occupied, clattered by, and I despaired of finding one that was free at this hour. But at last another appeared and slowed.

“My friend is hurt and needs to go to hospital,” I called up to the driver. “She’s just at the corner, but I need help fetching her.”

He tilted his head back and looked at me suspiciously. “What’d’you mean, she’s ’urt? I ain’t takin’ ’er if’n she’s drunk, or just been roughed up by a customer—”

“She’s not a prostitute!” I retorted, my mind quick to assemble a story that would bend his sympathies toward us. “It’s her brute of a husband that’s to blame, when he drinks up every bit of money she earns taking in washing! I’ll give you an extra two shillings for the fare.” Still he seemed undecided. “Please. If she stays out all night, she’ll be dead by morning.”

He grunted and began to climb down from his box. “Where is she?”

I pointed. “At the corner, just there. On the ground. But be careful—her arm may be broken.”

His eyes narrowed, and I thought I saw a glimmer of curiosity, or perhaps disgust at the thought of a man who would do such a thing. “You stay ’ere with my ’orse.”

I nodded and caught the reins he tossed me. The mare took not the slightest notice, and I stared at the entrance to the alley until my eyes burned.

Finally, he emerged, carrying Marceline, and together we put her inside the cab.

“Which ’ospital?” he asked.

“Charing Cross, please, in Agar Street, off the Strand.”

We rolled forward, with me cradling Marceline close, trying to absorb the jolts of the ride. But as we drew up to the tall iron gates of the hospital, I realized my own predicament.

I knew there would be a guard to receive her, for as Dr. Everett often said, disease pays no heed to regular hours. But if I took Marceline inside, I’d have to answer questions, and I wouldn’t be able to keep up my disguise around people who knew me. I had been here too many times to help the doctor with his books and play the piano for patients.

The cab halted, and I dismounted on the right side and remained in the shadows, close to the wheel.

“I don’t want to be seen,” I said to the cabdriver. “Can you tell the guard that you found her?”

He snorted and muttered something under his breath but went silent as I handed him the fare plus the extra I’d promised.

“The bell is just there.” I pointed to the metal box and hurried away to the far side of the street. From the shadows between two buildings, I observed the guard, Mr. Oliven, emerge from the guardhouse. He and the driver exchanged a few words, and Marceline was shifted out of the cab and into his arms.

She was so limp and motionless that she might have been dead. A hard lump filled my throat as I watched him carrying her across the lit courtyard to the front door, and I remembered the night I’d met her.

It was my first performance at the Octavian. I’d only had a few minutes before the show to leaf through the music Mr. Williams had given me, and I hadn’t noticed that two pages were missing from the final number. When we reached that part of the song, I’d fumbled and improvised, but it was clear to anyone watching that I’d made a mess of it. I’d barely closed the piano lid and gathered my things when Mr. Williams burst into the alcove red-faced and shouting. When I finally managed to get a word in edgewise to explain that the pages had been missing, he’d motioned violently toward the piano bench. “You fool! Why didn’t you look in there? If you do anything like this again, you’re finished!”

He’d stormed off, leaving me shaking. Finally, I opened the bench, and through my tears I saw the two missing pages.

Why on earth hadn’t they been in the portfolio where they belonged?

From the direction of the stage came footsteps and then, “Don’t take it to heart. He’s always bawling at someone.” The voice was feminine and musical, with a slight accent.

I looked up, blinking the tears back.

The young woman from the trapeze act stood at the threshold of the alcove. While she had been flying through the air, she looked lithe and powerful; up close she was petite and very pretty. Her long black hair was still coiled in braids around her head; her expression was sympathetic, and her eyes were dark and sparkling.

My attempt to recover my poise failed, and her lips parted in surprise. “Why—you’re a woman!”

I swallowed hard and nodded, too wretched to even attempt the lie.

“Don’t worry.” She came close enough that she could murmur. “I won’t give you away. It’s hard enough for us. If I could masquerade as a man, I would. But we get paid more if I’m in this.” She glanced down at her pale pink costume, which, in contrast to Sebastian’s severe black one, left her legs and arms bare and was embroidered with sparkling threads.

“And I get paid more if I’m in this,” I said, gesturing to my masculine garb.

She laughed.

I nodded toward the curtains through which Mr. Williams had vanished. “Does he really always shout like that?”

“Every night that I’ve been here,” she said airily. “I remember once I was late to the stage. He all but had a fit,I tell you! He looked like a rabid dog, with spit flying out of his mouth. And the horrid names he called me.” Her delicate eyebrows rose. “I thought Sebastian was going to hit him.”

A rueful laugh escaped me. “Well, I can’t hit him. I need the money.”

“So do we,” she said cheerfully. “So does everyone, I dare say. But he’ll forget it by tomorrow.”

“I hope so.”

She gave a crooked smile that revealed small white teeth. “My name’s Marceline. What’s yours?”

“Nell. It’s short for Elinor.”

She tipped her head toward me, her eyes thoughtful. “Well, Nell, I’ll see you tomorrow. And really, don’t worry about old Williams.” With a graceful little wave, she turned away and went to stage left where her brother was waiting, coat in hand.

I’d felt so grateful to her. I might not even have had the courage to return the following night if it hadn’t been for her kindness.

As the hospital door closed behind my friend, I blinked back the tears pricking at the corners of my eyes. What vile person had beaten her and dumped her in that rotten little street? And where was Sebastian? Had something similar befallen him? Did he have any idea what had happened?

I waited until a light appeared in the room used for admitting new patients. I imagined the night nurse settling Marceline in a bed; then, feeling relieved that she was safe for this night at least, I started for home.

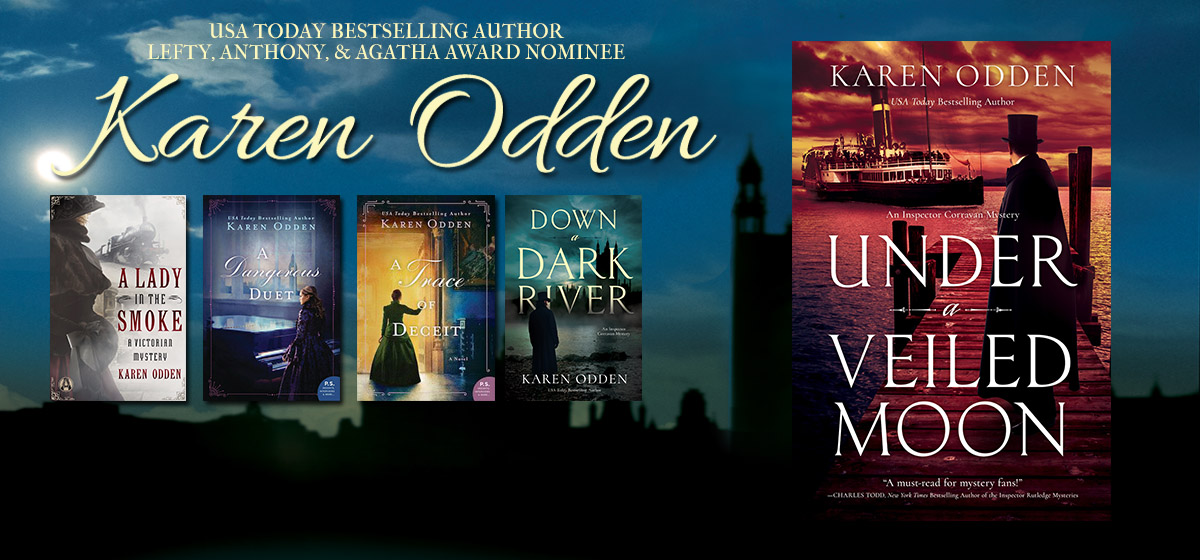

Ready for more? A Dangerous Duet by Karen Odden is available from your favorite bookseller!