On the morning of my 29th birthday, November 11, 1994, I was standing in the main auction room at Christie’s. The elegant space was crowded for the rare book auction scheduled to begin at 10 o’clock. There was an elevated stage at the front, and Stephen Massey, the head of the Rare Books department, had taken the podium. I was standing along one wall with some other Christie’s employees. Rows of chairs extended across the floor, filled with potential buyers and some gawkers. On the opposite wall was a bank of tables draped with black fabric, with phones for other Christie’s employees who’d be taking the bids of people calling in. The star of the auction that day was Leonardo Da Vinci’s CODEX HAMMER, one of his notebooks, 32 pages, written right to left, in his mirror handwriting, and featuring the famous image of the Vitruvian Man, among others (illustration). People who attend Christie’s auctions are generally well behaved. They speak in soft tones, if they speak at all. No one shouts out or flaps their paddle around. But that day people could not stop talking; they couldn’t contain themselves. The auction began, the lots containing rare books and manuscripts, signed copies and first editions, and most of them sold well. But everyone was waiting for the Da Vinci notebook.

People who attend Christie’s auctions are generally well behaved. They speak in soft tones, if they speak at all. No one shouts out or flaps their paddle around. But that day people could not stop talking; they couldn’t contain themselves. The auction began, the lots containing rare books and manuscripts, signed copies and first editions, and most of them sold well. But everyone was waiting for the Da Vinci notebook.

I believe the presale estimate in the catalog was somewhere in the range of 5 million. Between buyers in the room and on the phones, the bid began to climb: 6 million, 6.5, 7, 7.5 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20 …. By this time it was down to two bidders, one in the room and one on the phone, and the employee at the phone bank just kept raising her hand. Eventually the hammer came down at 28 million dollars to a phone bidder whose identity was kept confidential. Later, I heard one of the Christie’s employees say, “It went to someone named Bill Cates.” His friend replied, “Not Cates, Gates. I think he does something with computers.” It’s hard to remember but back in 1994, Windows 95 was still months away, and Bill Gates wasn’t a household name yet.

The reason I’m telling this story is because it was the first time I felt down to my bones the way suspense and story could swirl around art.

I wasn’t at Christie’s because I knew anything about art. I was a media buyer, in charge of purchasing print ad space for the sales Christie’s held over the course of the year, for everything from paintings and photographs to silver coins and Faberge eggs, Chinese and Latin American art, Hollywood collectibles and antique furniture. I placed ads in over 50 publications including the New York Times, Architectural Digest, the Newtown Bee, and Art and Auction. Because I was buying ad space, I had to read these publications in order to know what art to advertise where, so that’s what I did. For the first few weeks, I sat in my little cubicle and read magazines and newspapers. It was fun. (My dad always said, you’re never going to find a job that pays you to read! Ha!) So like many things in my life I came to art—or rather, to my appreciation of art—through reading stories. About the pieces of art smuggled out of Wartime Germany by an American soldier, only to be found by his grandchildren forty years later, after his death. About the art heists and dramatic thefts out of museums. About the fire at the Pantechnicon in 1874 London, which destroyed $280 million worth of art and antiques (illustration). About the Renaissance painting by Cimabue that a 90-year-old Frenchwoman had hung over her kitchen stove for years because she thought it was a knock off. About the painter who fell in love with his subject and hid the finished portrait rather than selling it to her husband. And while I like art, it’s still the stories about it that fascinate me. Writing A Trace of Deceit, about the 1870s London art and auction world and a young woman painter at the newly opened Slade School of Art, was my way of sharing some of them.

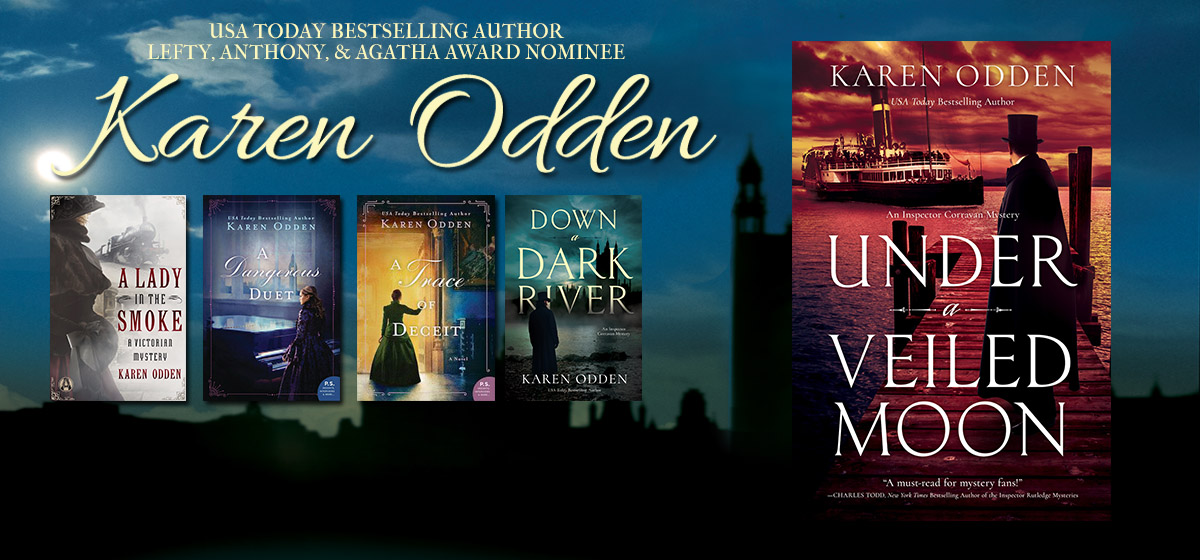

So like many things in my life I came to art—or rather, to my appreciation of art—through reading stories. About the pieces of art smuggled out of Wartime Germany by an American soldier, only to be found by his grandchildren forty years later, after his death. About the art heists and dramatic thefts out of museums. About the fire at the Pantechnicon in 1874 London, which destroyed $280 million worth of art and antiques (illustration). About the Renaissance painting by Cimabue that a 90-year-old Frenchwoman had hung over her kitchen stove for years because she thought it was a knock off. About the painter who fell in love with his subject and hid the finished portrait rather than selling it to her husband. And while I like art, it’s still the stories about it that fascinate me. Writing A Trace of Deceit, about the 1870s London art and auction world and a young woman painter at the newly opened Slade School of Art, was my way of sharing some of them.

Ann Marie Ackermann and I became friends after the publication of my first book, A Lady

Ann Marie Ackermann and I became friends after the publication of my first book, A Lady Holy sack of straw! (All right, all right, that’s what Germans say when they’re surprised.) That note looked, sounded, and smelled like forensic ballistics. The only problem was that forensic ballistics supposedly hadn’t been invented yet. Not for another half century.

Holy sack of straw! (All right, all right, that’s what Germans say when they’re surprised.) That note looked, sounded, and smelled like forensic ballistics. The only problem was that forensic ballistics supposedly hadn’t been invented yet. Not for another half century. Ann Marie Ackermann is a former prosecutor from Washington State now living in Germany, where she wrote the award-winning historical true crime

Ann Marie Ackermann is a former prosecutor from Washington State now living in Germany, where she wrote the award-winning historical true crime