Liverpool Street Station, London, May 1874

My mother’s nerves were brittle as a porcelain teacup worn thin around the edge, which is why she took an extra dose of laudanum before we boarded the train home that day. I doubt anyone around us on the crowded platform could have guessed that she had a tincture of opium and alcohol running through her veins at half-past eleven o’clock in the morning. Looking at her, they’d see only a well-dressed gentlewoman, her face tranquil, and her fair hair beautifully arranged under an expensive hat.

But I knew. In the ten years since my father had died, I’d learned how to recognize when she’d taken an extra sip from the brown bottle she kept in her reticule: by her dreamy silence, by the faint smile that came and went without cause, and a certain softness to her chin, like a blur in an unfinished portrait.

I glanced sideways. Yes, she was very different now from what she’d been a mere ten hours ago, when we were alone in our rooms—her voice hard, her face contorted with fury–

A shriek cut through the dull roar inside the station, and our train rounded the corner, the racket of the wheels driving the pigeons off the rafters and into a whirl of feathers. The engine came to a halt, belching steam and filling the air with the smells of coal dust and burnt oil.

“Up train to York,” bellowed the stationmaster, “running express to Hertford and stopping at all points north!”

Railway servants in red uniforms rushed to the first-class carriages with sets of wooden steps, and passengers started to disembark. In a few minutes, we’d be on our way out of this godforsaken city.

“Lady Fraser! Lady Elizabeth! Oh, my dears!” shrilled a woman’s voice.

I kept my face averted. I didn’t want to see anyone I knew. Please. Please just let us get on this train and be gone.

“Lady Elizabeth! I say, Lady Elizabeth!”

I sighed and turned to see a plump woman trying to shift her way through the crowd. What was her name? Miss Rush. She was one of my distant relations who had been at Lady Lorry’s ball last night. Her round face was splotched pink with the effort she was making to reach us, and I felt a pang of pity. She must exist on the farthest fringe of society, for apparently no one at the ball had felt there was any social currency to be gained by telling her the rumors about us. Otherwise, Miss Rush would have been watching us slyly and leaving us quite alone.

“Are you taking this train home, then?” she asked breathlessly as she drew near.

I forced a smile. “Yes, we are. And you?”

“Oh, yes.” Miss Rush gave a quick, curious glance at my mother, who was staring into mid-air. Then she gazed wistfully at the train. “But of course you are riding in a first-class carriage! Alas, when one is retrenching, every farthing matters, as you know—but, then”—a little, tentative laugh, and a wave toward the second-class carriages, close behind the smoking engines—“you wouldn’t know, my dear—but no matter! I’d have endured any sort of travel for such a ball! I didn’t see you dancing very often; but when you’re married, I’m sure you’ll have a ball just as beautiful.”

I winced and looked away. The first passengers were being helped aboard, and people around us were beginning to push forward. I took my mother’s arm and said apologetically, “I’m afraid my mother is very fatigued. We should go to our—”

“And your cousin looked just as a bride should with her new husband!” She leaned forward as if she were about to confide a secret. “I’ve heard that Americans are brash and uncouth, but he wasn’t dreadful at all! In fact, he was—”

I let the crowd draw us apart, raised my hands helplessly, and called over my shoulder, “I’m sorry we must go. I wish you a pleasant trip home.”

“Oh! Of course! Goodbye, dear.” She smiled brightly, like a child pretending not to be hurt, and gave a little wave as we turned away.

Something inside me shriveled at my selfishness, for not taking her hint and inviting her to share our compartment. But if I had to listen to her prattle on about that wretched ball for hours, I’d throw myself off the train like one of those mad people I’d read about in the papers.

“Miss?”

One of the railway servants for the first-class carriages had his gloved hand out, waiting to help me aboard.

Mama was already inside, and as I stepped up, I could feel the vibration of the train under my feet. I followed Mama down a corridor so narrow that it was a good thing bird-cage crinoline skirts were no longer in fashion. Our compartment was the middle one of three and quite spacious, but the windows were small, and the green velvet cushions lumpy and frayed. On the backward-facing wall was a painted advertisement for Hudson’s Dry Soap that featured a busy harbor at sunset. Mama took the forward-facing seat near the door; I sat down between her and the window and closed my eyes. Even at rest, the train trembled with a fierce energy. Something near my ear rattled, and I opened my eyes to see one of the windowpanes jiggling against the frame. I put up my gloved hand to still it.

Through the dirt on the glass, I saw a figure on the platform that looked familiar, and my heart jumped.

Could that be Anne?

But my friend was supposed to be with her brother Francis at Venwell, their family estate in Scotland, for another fortnight.

I found the least grimy part of the window and peered out. The woman had Anne’s dark hair, coiled in the same style Anne always wore and the same slim shoulders wrapped in a blue coat. As she turned her head to look at the train, my hand was already up to wave–

But it wasn’t Anne. Of course not.

The disappointment pushed like a weight at my chest. I leaned back against the velvet, watching the young woman disappear into the crowd of people, all shoving and bumping against one another, like sheep in a shearing corral.

If I’d had Anne with me last night, I could have borne it. When that first pair of ladies darted looks at me and raised their fans to hide their mouths, Anne would have raised her own fan and whispered things that would’ve helped me swallow down my growing discomfort. But the entire Reynolds family was avoiding the Season because of an awful article about Anne’s brother that had appeared in the Courier a few months ago. So I’d stood alone, half-hidden by a marble pillar, and tried to keep the color from mounting to my cheeks while I wondered what on earth people could be saying. I was an heiress with a respectable dowry of ten thousand pounds per annum. I was twenty years old, not unattractive (though I lacked the fair beauty of my mother), with a name and title that stood well up on the list of landed gentry, and no scandal attached to me. As such, I was considered a fine catch in the marriage market—as Anne and I joked dryly, much like tenderloin at the butcher. And it was only my third Season, so it’s not as though my goods were rotting.

I had opened my dance card and noticed that it was oddly empty. And then, as I stood with my gloved hand pressed against the pillar, I heard Lady Nestor say that she had it on good authority that my family’s fortunes were slipping, and my ten thousand pounds per annum was soon to be a thing of the past.

I felt a sick churning in my stomach, and the ballroom suddenly seemed unbearably hot. I slid farther behind the pillar, resisting the urge to find my mother then and there, to ask whether what Lady Nestor said was true. I forced myself to compose my face, to remain where I was, and wait the two agonizing hours until we were finally back in our rooms.

And then there were two more agonizing hours listening to her rage at me that yes, it was true—and wasn’t I sorry because now I would pay for my stupidity—I, who was selfish—selfish–selfish—always–

Our carriage rattled as heavy cargo doors slammed closed; the stationmaster blew his whistle again and made the last call for people to board. I turned to look at my mother. She gazed vaguely at the soap advertisement, her gloved hands resting on her reticule, the laudanum smile hovering around her lips. I didn’t know if I preferred her screaming at me or completely absent like this.

Over the years, I’d learned that when there was a raw edge to her rage, it was often because she had missed her laudanum, or because she’d drunk more than a glass or two of champagne. But her accusations from last night still hurt me, and frightened me too. I wasn’t such a fool as to believe that my personal charms were enough to preserve my place in the marriage market. Without a dowry, I would no longer be one of the choicer cuts of beef. I wondered bitterly what I’d be now. The skirt steak, perhaps, in need of a hearty sauce to conceal its indifferent quality.

I swallowed the lump in my throat and looked back out the window, wishing desperately that the train would pull out of the station. What on earth was taking so long?

The handle to our compartment turned with a sharp click, and the door swung in. A heavy-set, well-dressed gentleman entered our carriage and stowed his briefcase on the rack overhead.

How strange! We’d reserved a private compartment—at least, I thought we had. But perhaps this was part of our change of fortune, a small way that my mother chose to retrench, as Miss Rush put it. My mother merely smiled distractedly at him, and I didn’t want the fuss of calling a porter, or whomever one called in such cases. Without taking a bit of notice of us, he sat down opposite, facing the rear of the train, placed his hat on the seat beside him, folded his hands across his chest, and closed his eyes.

He would’ve caught Anne’s painterly eye. His bald head was egg-shaped, narrow at the top, and fuller at the bottom; he had eyebrows as bristly as Mr. Jaggers’s in Great Expectations, and his thin lips turned down sourly. He remained utterly still, except for his jowls, which shuddered as the train began to move.

Rain knifed against the windows as we pulled out of the station. Finally, after several weeks away, we were going home. I’d never liked London, with its rotten yellow air; its hordes of people and cabs and carriages that fought for space on the streets; the working men who walked with their shoulders hunched, as if merely getting through the day was a burden on their backs.

And the gossip that filled the air like mosquitoes over a swampland.

I’d never come here again if I could help it.

As the train sped up, the silver telegraph lines above dipped and curved faster than my eyes could follow, and the wooden poles blurred together. The rhythm of the wheels lulled me into a sort of stupor, and eventually I slept.

Then came a high-pitched screech of metal wheels on the iron track, and I was flung across the compartment before I could put up my hands.

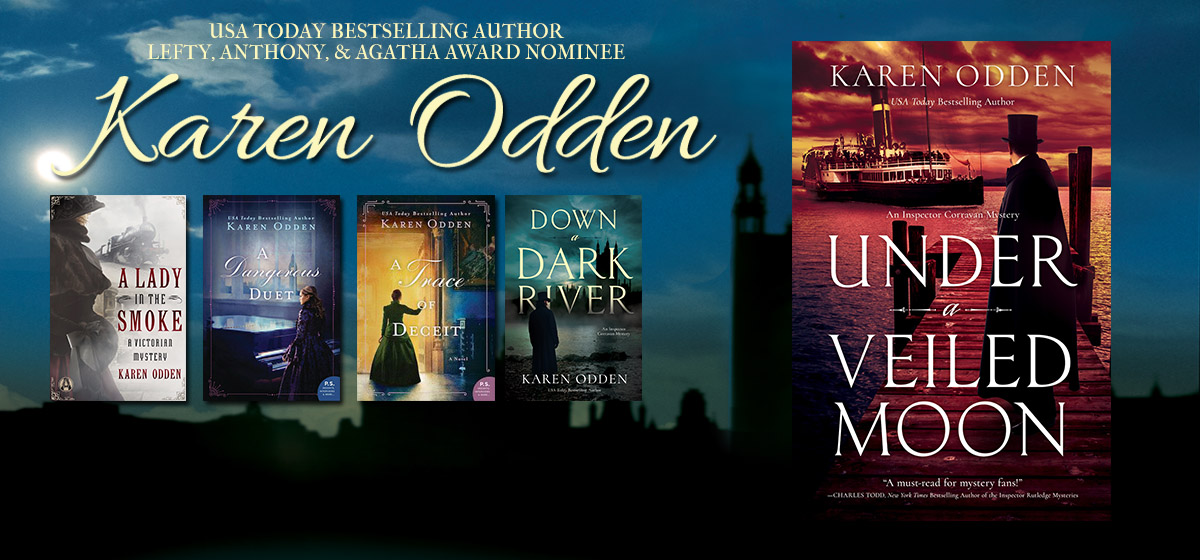

Ready for more? A Lady in the Smoke by Karen Odden is available on eBook from your favorite online ebook retailer.