This past weekend, I attended my first in-person Historical Novel Society conference. I served on a panel called “Historical Fiction Revolving Around Real-Life Crimes” with Nancy Bilyeau, Mariah Fredericks, and Weina Dai Randel (right to left). All of us began with a “true crime” incident – but it got me to reflect and go a bit “meta” about how I use that juicy morsel of history once I find it. How do I know it has the heft to be the core of a book? Or – more precisely – how do I give it that heft?

Step 1: Finding the nugget. My first step in using historical facts is to pay attention when something snags at me, pulls me up short during research, makes me do that Chandler Bing double-take — “Wait, what?” Someone said to me once, if a fact surprises and intrigues you, it probably will intrigue others. I find that surprise is especially valuable here, as a gauge for what to pursue. The energy that surrounds genuine surprise can light a fire in my brain and inspire me for 2 to 3 chapters, which is enough to get the ball rolling.

An example: As I was researching for Down a Dark River, I was reading a rather dry article about the minutiae of maritime law, and I came across a sentence that went something like this — “In the wake of the worst maritime disaster London ever saw, the loosely upheld traditions and conventions governing traffic were codified into law in the 1880s…”

That tidbit in the prepositional phrase stopped me dead. Wait, what disaster? I googled and found the story about the Princess Alice, which was one in a fleet of small wooden pleasure steamers on the Thames in the 1870s. On September 3, 1878, it was coming upstream by moonlight and was rammed by a 900-ton iron-hulled coal carrier, the Bywell Castle. This is somewhat akin to a railway engine slamming into a baby carriage. The Princess Alice broke into three pieces and sank almost immediately, throwing 650 passengers in the water. Most drowned — and in a cruel twist, because it was a pleasure steamer, akin to our hop-on-hop-off buses, no one knew who was on the boat. It threw London into a panic for days as desperate families and friends searched for survivors and then the bodies, which were scattered over miles of riverbank.

This was certainly a horrible but highly valuable nugget of history. But how could I give it big stakes? How could I best use it as an element in my book, beyond its sensation value?

Step 2: Find the extended meanings. I began to identify a few aspects of the world of 1878 London that give this event higher and more particular cultural meaning.

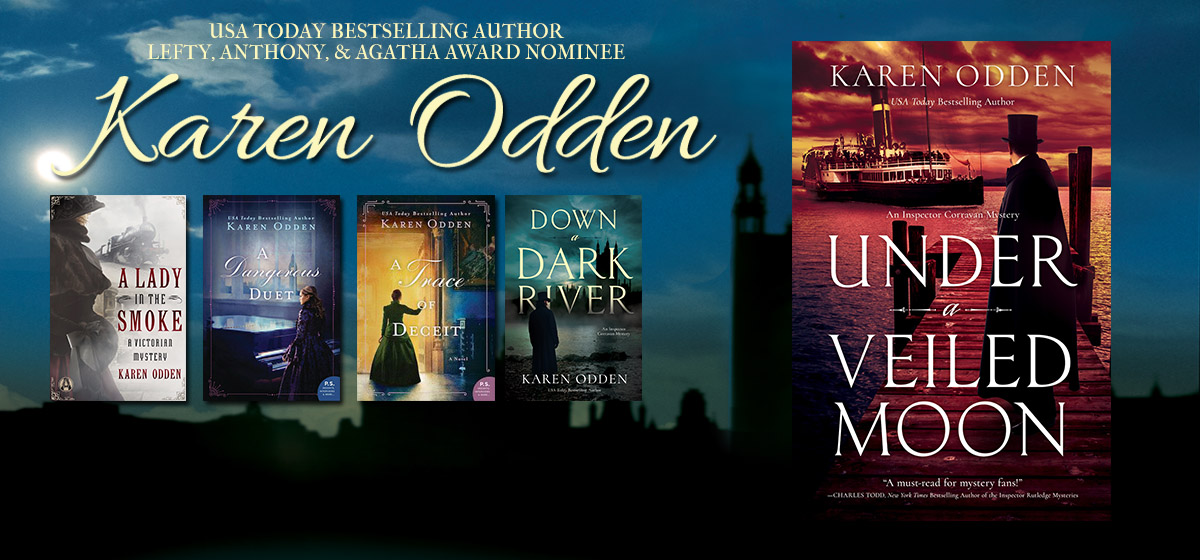

For Under a Veiled Moon, I came up with these:

(1) the collision between a huge metal boat and a small wooden ship suggested the clash between two different modes of production — namely, between mechanization and agriculture and between industrialization and cottage industries that had existed earlier in the 19th century.

(2) there were Irish crew members and Irish men and women on both boats; I thought I might tie this into anti-Irish prejudice that I’d been reading about (rabid and rampant in some quarters).

(3) there was still suspicion of Scotland Yard after a corruption and bribery scandal and public trial put four Yard inspectors in jail the year before, in 1877.

(4) the lack of passenger manifest, and no way knowing who was on the boat, suggests the depersonalization and anonymity felt by many individuals in the lower and middle classes in the enormous city of London; and the vanishing of the individual in large impersonal bureaucracies and cities (typical of modernity).

This is just my personal example, but I think one way to add depth to a novel is to identify the historical elements that add symbolic resonance and can potentially establish big stakes for a novel.

Step 3: Ask the “what if” question. Don’t be afraid to bring in another historical aspect to be the warp to your weft. For Under a Veiled Moon, I brought in the hundreds of London newspapers that printed rumors and misrepresentations in the aftermath. This allowed me to talk about Victorian (social) media. I departed from the truth in saying that London papers were all accusing the Irish Republican Brotherhood of sabotage. And I use my Author’s Note (Acknowledgments) as my get-out-of-jail-free card, explaining where been historically accurate and where I’ve taken liberties.

True history tells us that the Princess Alice/Bywell Castle collision was the fault of both ships: the Princess Alice was in the wrong place, the Bywell Castle was going too fast. But what if it wasn’t an accident? What if it was sabotage? Who would do such a thing and why? That’s the question that helps me discover my characters – the villains, the victims, the innocent bystanders, the protagonist, and the forces allied against him.

How do you use your historical nuggets? What are some that you’ve used? Or decided not to use?